Even a man, who is pure of heart, and says his prayers by night…

The Beast, he tells them, his voice dropping to a whisper that throbs, and no eye wanders. He has them in thrall. Watch for the Beast, for he may smile and say he is your neighbor, but oh my brethren, his teeth are sharp and you may mark the uneasy in which his eyes roll. He is the Beast, and he is here now, in Tarker’s Mills.

Stephen King, ‘May,’ Cycle of the Werewolf

WARNING – Contains Spoilers for the Werewolf’s Identity.

In Stephen King, there are major works and minor works. Cycle of the Werewolf is a work so tiny it barely registers at all.

King by this point in his career was a publishing star. With Christine, his previous book, he had declined the usual author advance on royalties he received previously (accepting only a single dollar) in favour of earning out his royalties and getting money from that, as well as having sold the movie rights pre-publication. Most authors don’t ever do that, or can even afford to, so this shows a tremendous amount of confidence in his ability to sell at this point in his career. Yet at the same time, he wanted to try to do things differently. He had his pseudonym going on in the background, and The Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger had been published in instalments before being published in limited editions that most of his fans weren’t even aware existed until Pet Sematary, his next book, listed it.

Cycle of the Werewolf exists in that same publishing experimentation that King occasionally likes to play with. He was approached, whilst very drunk apparently, to write a horror themed calendar (the later adaptation Silver Bullet may be the only film ever to be adapted from a calendar, but I still reckon It’s A Wonderful Life has it beat being adapted from, essentially, a greetings card). He quickly found the 500 word limit for each month too much, and expanded it, slightly, to be a book.

King is not totally unfamiliar to comics. He had read them in his youth, he had made Creepshow, and he was not far off writing a couple of pages of the X-Men with Bernie Wrightson for charity (which, as it’s only a couple of pages I’m not covering it, but can be found here). Many years later, The Stand and The Dark Tower would be adapted by Marvel (click the links for more information, as again, I’m not planning to cover them). But Cycle of the Werewolf is the closest to getting a full comic from King.

The book is thin (I think calling it even a novella is generous), but it does have some similarities with some of King’s other work. Though it begins to become repetitious by June, the set ’em up, knock ’em down way of swiftly entering and exiting characters effectively builds the character of Tarker’s Mills, like so many towns before and after in King’s work. That it is a town with hidden secrets recalls to mind mostly Jerusalem’s Lot of ‘Salem’s Lot, and there are many other parallels besides that: a priest with a darker secret, an abusing bastard, a monster that strikes only at night. The tropes of King’s writing are all present and accounted for, whipped through at lightning speed.

Despite its brevity, there are some interesting things played about here. The holdover that the book be written as a form of calendar gives the story an immediate structure different to others we’ve read, creating a series of implausibly linked vignettes (the cycles of the moon has no resemblance to reality) that dip in and and out of a narrative that feels breathless. You could read this over an afternoon.

Utilising a werewolf is also unique for King. King loves vampires, but seems to rarely use werewolves as an actual monster. Werewolves are hard to get right in practically any medium outside of folklore, but using it as a vehicle to tell what is essentially a murder mystery is an inspired idea and one I’m not sure I’ve seen used elsewhere with werewolves. Also, the manner in which the reverend is turned into werewolf by plucking flowers shows King’s knowledge of werewolf lore beyond the classic viral, transformational nip on the arm, making this particular werewolf a closed loop type.

But as mentioned, there’s not much else here in literary terms. Werewolves, like vampires, can be potent metaphors when used correctly, and having the werewolf here be a man of the cloth is a rich idea that doesn’t really get explored. The book isn’t trying to do that, and so would be unfair to criticise it for those reasons, so instead let’s look at it for what it was intended: a vehicle to show off Bernie Wrightson’s artwork.

Wrightson has had a long career in comics, most notably co-creating Swamp Thing for DC, but is known for his grotesque horror art. Among his fans, he can include such talents as Guilermo del Toro, Neil Gaiman and Mike Mignola, and his artwork is known for rich, intricate linework full of detail that rewards a studied look. Wrightson worked with King a couple of times in his career, most notably on this book, but also providing art for the comic of Creepshow, illustrations for The Stand‘s extended 90s edition and the Dark Tower book Wolves of Calla (art here), as well as illustrating a TV Guide cover for King’s TV version of The Shining.

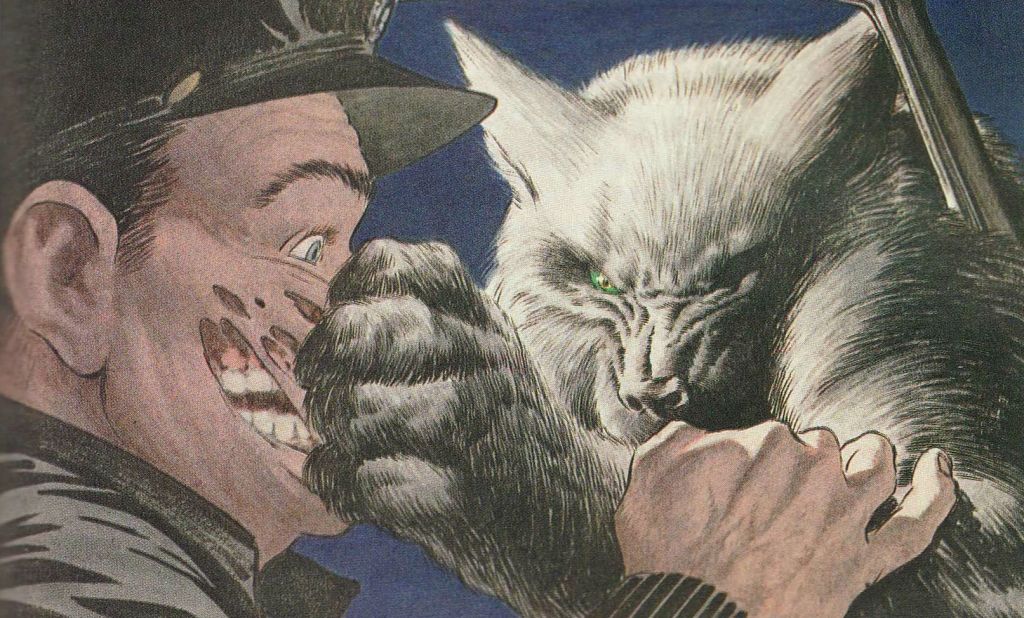

What I particularly like about the art here is how it stand in contrast to King’s writing. The writing is at times lurid, but the art has a cool, detached perspective. Another artist would have been tempted to go for the crazy angle, lashings of blood or intense close-ups. Though Wrightson does not shy away from bloody detail (see his September piece with the slaughtered pigs), his artwork doesn’t dwell on it. Rather, we are helpless observers. Because it does not sink into the horror, the distance it has instead heightens it, as we are left to observe something beyond our control. The illustration for June, with the werewolf menacing the diner cook, is a perfect example. It has no blood, no tearing of skin or wrenching of bones. But its mood is that of just before the real horror begins. Even the image at the top of the essay with skin tearing and all, is a mere millisecond before the blood begins to pour. We always seem to be just missing the carnage, before or after. The pictures Wrightson creates don’t show us what is happening, but promise something will (or has) happen, and that you don’t want to see it when it does.

Personally, the images I found most eerie are the empty images that introduce each month. Detailed black and white images that show landscapes where your eyes search out for the hidden details: a tuft of fur, a glowing eye, a scratch in the bark, some sign that the werewolf is close by. They do a tremendous job of creating a mood for the book that King’s writing, in his brevity, can’t match in the same way. My favourite illustration is November. There is something so intricately evil in that image, the werewolf in the snow with its blasted eye staring out at the reader just after its kill. It’s probably the bloodiest image in the collection, but we have missed the violence. All we see is its after effects, and are forced to imagine what dreadful circumstances led to its happening.

So, in short: come for the King, stay for the art.

Observations and Connections

If there is anything, I didn’t pick up on it. The location, Tarker’s Mills is also a Maine town, but so far as I can tell never shows up again, or is even referenced.

UP NEXT: Make sure to keep your dog on a tight leash, as we pass by Pet Sematary.

Tarker’s Mills is west of Chester’s Mills (Under the Dome). “Chester’s and Tarker’s were sometimes known as the Twin Mills”

LikeLiked by 1 person

That would make sense. I haven’t read Under the Dome yet, so it’s a connection to look forward to. Thanks for stopping by!

(oh my god Bev Vincent commented on my dumb stuff)

LikeLiked by 1 person